That most of us live in a low-value, low-trust economy of shoddy goods and services hidden beneath high-tech frictionless, faceless transactions is not recognized.

Social trust manifests in all sorts of ways, and it’s often amorphous and difficult to measure. We sense its presence or absence, but exactly what is it? Is it our trust in strangers, or our trust in institutions, or a warm and fuzzy feeling that our society isn’t falling apart?

In several critical ways, social trust isn’t warm and fuzzy, it’s all about the money, honey. In high-trust societies, transactions are frictionless and low-cost. In low-trust societies, transactions must go through multiple levels of verification, trusted third-parties, etc., each of which is costly.

Correspondent Bruce H. illuminates the differences between high-trust and low-trust transactions:

“There must be a high degree of social trust in order to make business transactions. If you think the other person is likely to take the goods and not pay, you are not likely to engage as freely, and the “shadow work” of ensuring that a transaction is honored drains the economy.

In cultures where cunning and deception are seen as laudable, business transactions are slow, proceeding only carefully, in a time-consuming way because both parties have to ensure the other’s compliance at every phase of the arrangement. This is costly.

In cultures where personal honor take primacy, a quick handshake is sufficient and work can begin immediately, confident that payment or the exchange will proceed to both parties benefit.

That, in essence, is what my father told me about his experience of doing business around the world.

There are places where you just discuss what is needed and agree on a price shake hands and write it down, there are places where you make sure the paperwork is in order and signed before you work, there are places where you make sure they have the money they claim they have and do all the paperwork and get some up front, and there are places where you make sure the money is in the hands of some secure third party (which, of course costs money) before you sign any agreements.

This also absolutely correlates between the relative wealth of these places. The places with the least trust are the poorest, those with the highest levels of trust are the wealthiest, all other factors being equal.”

It’s the money, honey: low-trust = poor, high-trust = wealthy as cumbersome, time-consuming costly transactions suck the life out of an economy.

There are other financial aspects of high-trust / low-trust societies. In high-trust economies, transactions are the core of the economy. The vast majority of transactions occur online or with complete strangers. In low-trust economies, trusted relationships are the core of the economy, and so business is conducted in much smaller circles which are connected by trusted go-betweens, often related by family or other close social ties.

This relationship-based economy was the model used in the ancient world, and it works well when trade and communications took months or even years. It works well on high-value transactions, for example, ships carrying luxury goods long distances. It works less well in a globalized, commoditized economy where the volume of transactions and business is enormous and covers a range of goods and services.

We can understand the U.S. economy as bifurcated into high-trust / low-trust segments which are difficult to tease apart unless we analyze the society and economy through the lens of class, an unpopular analysis in our supposedly classless culture.

High-value goods and services still tend to function on the level of relationships, while the shoddy, low-value goods and services are strictly transactional. The wealthy have connections, the rest of us get automated customer-service apps.

The wealthiest few reap fortunes from the low-value automated transactional economy that they don’t have to endure.

Consider the “value” of an elite university education. The cost is higher than a standard-issue university, but not that much higher. Compare the student who spends $100,000 obtaining a diploma from a second-tier “good” university, and one that spends (or gets scholarships) $150,000 to graduate from an elite university. The difference is in reputation, of course, and entree to elite institutions, but also in the relative ease of making connections.

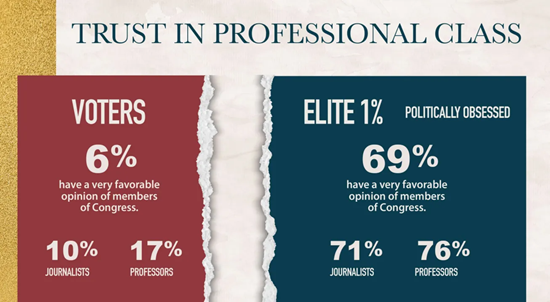

On rare occasions, outlier institutions such as Black Mountain College (1933-1957) offer unique opportunities for commoners to make valuable connections with luminaries, but as a general rule the “high value” goodies are reserved for the elite, which is why the top 1% has great trust in the same institutions that the bottom 99% have lost trust in.

That most of us live in a low-value, low-trust economy of shoddy goods and services hidden beneath high-tech frictionless, faceless transactions is not recognized, much less understood as a manifestation of wealth-income inequality. Yes, we trust institutions: we trust them to rip us off, ignore our queries, mess up simple transactions, sell us rubbish that falls apart or is “no longer supported,” stripmine us with hidden fees and burden us with endless shadow work to keep all their kludgy apps and digital services functioning.

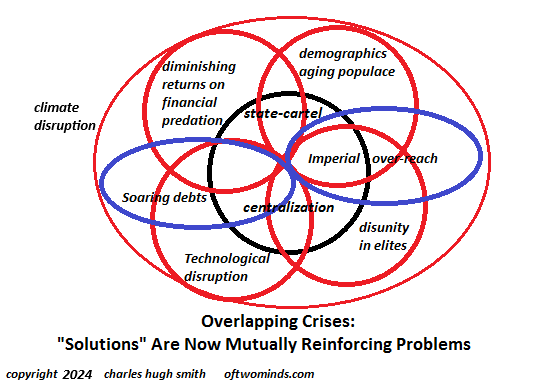

This raises a question: what happens in a society of intertwined high-trust and low-trust when polycrisis starts applying great pressure on social coherence and institutions?

Those living in a high-trust circle of relationships and connections will do just fine, the rest of us in steerage will be on our own. It’s a good idea to start forging our own network of trusted, high-value connections because “when you’re thirsty, it’s too late to dig a well.”

New podcast:

How Asset Deflation Could Play Out (35:37 min)

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18,

(Kindle $8.95,

audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022)

Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me

(Novel) print $10.95,

Kindle $6.95

Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can’t Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal

$18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook;

audiobook

Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States

(Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook)

Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker’s Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet

(Kindle $8.95, print $20,

audiobook $17.46)

Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook)

Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel)

$4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print);

read the first chapters

for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print)

Read the first section for free

Become

a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email

remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

| Thank you, Sebastian S. ($70), for your superbly generous subscription to this site — I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Phil ($7/month), for your magnificently generous subscription to this site — I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

| Thank you, Dan G. ($70), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site — I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Zamora1501 ($70), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site — I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |