Why is any reduction in consumption posed in terms of unbearable sacrifice, when no sacrifices are necessary to consequentially reduce consumption?

When we think of the word power, we associate it with external forces: energy, technology, the government, etc. But our own choices of behavior are a great power that’s all ours. Collectively, our choices of behavior set the direction of our culture, economy, society and political order.

I have a simple standard for the value of information / knowledge: is it actionable? Meaning, does this content give me anything that I can apply to my own life in the real world by modifying my behavior?

This is of course why we turn to YouTube University: we need to fix / repair something, and we seek actionable instructions on how to proceed as effectively as possible.

Some readers accuse me of living in an alternative universe, and they’re correct. I am skeptical of all received wisdom, be it conventional or alternative, and I prefer to test things in the real world myself via experimentation and data collection–what’s known as the scientific method–and to think things through myself rather than accept someone else’s account or explanation.

We all know diet and fitness are both behavior-based. We choose to eat certain things and avoid other things, and we either have a fitness routine or we don’t. We also know that diet and fitness are minefields of inter-connected influences, cultural, experiential and psychological, and so our conscious decisions about our behavior are often over-ridden or undermined by other dynamics.

Nonetheless, we still have the power to choose behaviors, and we can test the effectiveness of various modifications in our behavior.

For example, I’ve been running a decade-long experiment on the effect of my weight and general fitness on the metrics of blood pressure and cholesterol, both of which are prone to being elevated in my case. I’ve found from observation and data that getting lean (less weight, less fat, more muscle) has dramatically positive effects on my blood pressure and cholesterol, as well as on the critical ratio of triglycerides divided by HDL, so-called “good cholesterol,” a ratio which is a measure of general metabolic health. Ideally, the triglycerides / HDL ratio is under 2.0. Mine is 1.3.

The goal here is obvious: to maintain general good health because that makes life more enjoyable. If we define general good health as not needing any medications to maintain our health, then the goal is to not need any medications–and since my metrics are all in the acceptable range, I don’t need any medications.

These effects are testable. Since there is no one metric that tells us everything we need to know about our health–I consider agility and endurance, harder to measure than standard metrics, as important as any conventional test result–we can track a variety of data against modifications of our behaviors.

Consider water consumption, an easily measured metric. Water is cheap in the U.S., and so few people think much about their use of water, or how their behavior influences their consumption. Since we lived on catchment–the water supply depends on rainfall, which varies–we’re trained to avoid wasting water. (I also lived for months in a micro-house without electricity or water, and we hauled all the water we used in 5-gallon buckets from an agricultural ditch. That will quickly make you value water in a new way.)

Our two-person household uses 1,500 gallons a month, of which 20% to 30% is for watering our vegetable gardens. So our household use is about 1,200 gallons a month, or 20 gallons per person per day (40 X 30 days = 1,200).

The average water consumption for households in Hawaii is around 6,000 gallons per month, which translates to roughly 144 gallons per person per day.

So we’re using 25% of the average household, which includes many single-person households, and about 15% of the average daily use per person. Yet we sacrifice no conveniences or comforts. We have a washing machine, we take daily showers, we prepare three meals a day at home and wash a lot of dishes, and so on.

The difference isn’t generated by sacrifices, it’s generated by simple behaviors. We simply avoid wasting water.

Now consider electrical consumption. This varies by region, of course, and whether the stove/oven, heating system and water heater are fueled by gas/oil or by electricity. In our case, our stove is gas and our water heater is electric.

The average electricity consumption for households in Hawaii is around 515 kWh per month, lower than mainland states due to the lower needs for heating and cooling.

As an experiment, I set up 400-watt solar panels (about 1/20th the average rooftop system) and ran our electronics off the battery/solar panels for a month. The battery is 1500 watts, roughly 10% of a Tesla Powerwall battery (13.5 kwh). By electronics I mean the modem/router, multiple laptop computers, printer, etc. The goal was to see how little electricity we needed to run all the comforts and conveniences of a middle-class household.

We also turned off our water heater after our evening showers. This takes less than a minute. We sacrificed nothing, as the water stays hot enough for all purposes all day.

We consumed 2.4 kwh per person or 4.8 kwh per day, 145 kwh per month, down from our previous usage per month of 180 kwh. While we already avoided wasting electricity, we have all the electricity-powered conveniences of middle-class life and use them in the usual ways.

We used 28% of the average household in our region. We sacrificed nothing, and generated at most 10% of our own electricity with the modest PV panels. Before the experiment, we used about 35% of the average household consumption. We lowered our usage by nearly 20% with modest behavioral changes and a PV array 1/20th the size of the average rooftop array.

This raises significant questions about our economy, our runaway costs of living and our lifestyles. Healthcare consumes almost 20% of our nation’s enormous GDP. How much could we reduce the burdens of cost and ill-health with very basic, nothing-fancy modifications of our behaviors? How much could we reduce our consumption of water and energy with very basic, nothing-fancy modifications of our behaviors?

This raises another question: why is any reduction in consumption posed in terms of unbearable sacrifice, when no sacrifices are necessary to consequentially reduce consumption? Behavioral modifications of the sort described above exact very little from us. Many require very little time and extra effort, and those that do demand time and effort–a daily walk and eating only real food prepared at home–have outsized positive effects that would be considered miraculous were they contained in a pill.

Is squandering resources and health considered some sort of birthright, such that reducing waste and conserving what’s valuable sparks our indignation? I confess to seeing little value in indignation at the possibility that squandering valuable resources needlessly (including our own health) might some day exact a price we find excessive.

We want technology or the government to assure our lifestyle can continue unhindered, but what about the immense power of our own choices of behavior? Do they play no role at all?

In the current zeitgeist, I guess these questions place me squarely in an alternative universe. One reader said this made him sad. I’m not sure who should be sad for whom. If I can live in middle-class splendor using a fraction of the resources others consume, I don’t discern any source of pity in my alternative universe.

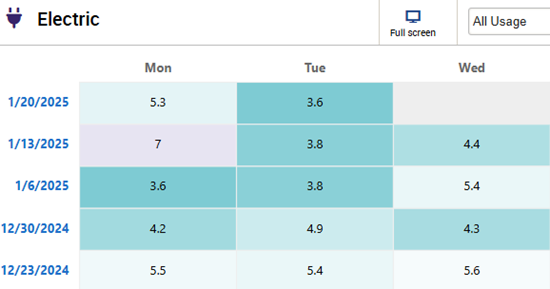

Here’s a snapshot of our daily electrical consumption, courtesy of our utility.

New podcasts:

KunstlerCast417: Charles Hugh Smith, Progress and Anti-Progress (1 hour)

Charles Hugh Smith on the Extremes in the U.S. Economy and Markets. (26 min)

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century

print $18,

(Kindle $8.95,

Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024)

Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18,

(Kindle $8.95,

audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022)

Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me

(Novel) print $10.95,

Kindle $6.95

Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can’t Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal

$18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook;

audiobook

Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States

(Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook)

Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker’s Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet

(Kindle $8.95, print $20,

audiobook $17.46)

Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook)

Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel)

$4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print);

read the first chapters

for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print)

Read the first section for free

Become

a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email

remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

| Thank you, Bruce T. ($70), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site — I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, Scott ($7/month), for your superbly generous subscription to this site — I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

| Thank you, Barb2K ($70), for your magnificently generous subscription to this site — I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Thank you, P.B. ($70), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site — I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |